TIP in Italy – Antonio Fava and “Commedia dell’Arte”: the birth of professional theatre and its enduring legacy

After his live presentation during the Digital Coffee Talk organised by E35 Foundation in collaboration with the MaMiMò Centre of Reggio Emilia on November 2023 through the Theatre in PALM project, Maestro Antonio Fava explores even deeper the history and evolution of “Commedia dell’Arte”.

The phrase “commedia dell’arte”—now referred to as Commedia dell’Arte—is not the original definition. It first appeared in Carlo Goldoni’s Il Teatro Comico (1750), where he expresses his ideas and condemns the very existence of the so-called “Italian comedy,” which, for him, was vulgar and approximate.

However, “commedia dell’arte” is what we now call “professional theater.” It was referred to as commedia to signify actors in actio, and “art” to mean a profession, trade, or paid work. The term emerged in the 1530s, although the exact year remains unknown. We do know that in 1538, an Italian histrion named Mutio was active outside Italy, in Spain and possibly later in France. From Spanish accounts, we understand that he performed “in the Zannesque or improvisational manner.”

1538 marks the earliest historical reference to place Commedia within its origins. However, it is inconceivable that Mutio invented the form on a specific day of that year and immediately began traveling across Europe. It seems reasonable to suppose that the early 1530s marked the birth of the Arte and the profession of acting.

In Commedia, the script and direction do not exist in the traditional sense. The final text and direction are the result of an agreement between actors, in a collaborative effort based on individual specializations (each actor’s character), mutual understanding (“affiatamento”), and the use of “modules”—whether expressive, action-based, or subject-based—that appear uniformly across all “different” comedies. Consequently, the script of Il Servitore cannot be classified as “commedia dell’arte”: it is written by the author once and for all, and must be respected by the actors at every performance, with lines and actions memorized and followed precisely.

Place of Performance

Nowadays, it is mistakenly assumed that Commedia dell’Arte is “street theater.” This is not the case. While many historical images show actors performing on a stage set up in a square or in a large space like a busy marketplace, there are far more images depicting the zannate performed inside equipped theaters, in salons adapted as theaters, and in indoor spaces suitable for theatrical use. The choice of “street” images is ideologically motivated, as there is a romanticized desire to suggest that Commedia belonged in the streets by vocation.

The expression used by the Comici, which has the same meaning as the modern “Tonight, we perform,” is well documented: “We go to the stanza (or stanzone)”. Thus, performances were not outdoors but in enclosed spaces, often grand and sumptuous salons belonging to wealthy patrons. For example, the Gelosi was performed in 1589 in the Salone dei Cinquecento at the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence, which was adapted for the scenic action and the comfort of the audience.

If, with the early Zannesca, the new entertainment professionals performed outdoors, it was because the “theatrical circuit” simply did not exist. The Comedians of the Arte adapted wherever they could create an environment favorable to the performance and to the audience’s attention. It could be the case of protected and isolated spaces within the city, places that were not or scarcely frequented, where they promoted the performance through “parades” in costume, informing and inviting the public; but also in certain “ancient ruins,” such as the Arena in Verona, where theatre companies of the Arte could control the audience, allowing only paying spectators to enter. This nascent entertainment industry quickly led to the creation of venues specifically designed to host performances: theaters. It is Commedia dell’Arte that sparked this need, quickly followed by Recitar Cantando, Melodramma, and Opera.

Commedia dell’Arte is Professional Theater. The term “Commedia” referred to Theater; at the time, the word “theater” did not refer to the art of acting, but to the venue for a specific event—the theater of a battle, a scandal, a ceremony, or a disaster. Commedia did not refer to a “theatrical genre”; it referred to a performance by actors who were professionals in Arte.

The professional logic entails obligations, rules, and actual laws that structure the form and distribution of the “show product.” These include:

- Specialization: each actor specializes in a specific character, present in all the “fabule”. They will play this character throughout their entire professional career. These recurring characters are known as the Tipi Fissi, which include:

- I° and II° Zanni: Characters who would like to sleep and eat but are instead overwhelmed by their masters’ troubles, the Vecchi and the Innamorati.

- Dottore and Magnifico: Two Vecchi, wealthy, widowed men, always in love with a young woman, creating turmoil for the Innamorati.

- Innamorati: A young man and woman, each the child of one of the Vecchio, perpetually in despair but always revived for the obligatory happy ending.

- Capitano: A braggart, a boater, and a charmer who infiltrates situations to gain benefits at both the table and in bed.

- Improvisation: improvisation is not “whatever comes to mind at the moment”; it is a method of writing. The actors, together, follow the scenario, where the fabula is explained in detail, and perform it, cooperating and fitting together, until they reach the final result, which includes both words and actions.

- Multilingualism: Commedia dell’Arte originates in a region where a certain dialect was spoken, and the Zannanti perform in the language of the audience, which was also their own. The professional logic required actors to “tour” in order to work year-round, moving to areas where different languages were spoken. Over time, a pattern emerged: each character spoke a different language (Lombard, Venetian, Emilian, Tuscan, etc.), which acted as a key to understanding the performance, depending on the location and the audience. One language, one character. Thus, Commedia became “European,” assigning each character a language based on their specific audience. The most common languages were French, Spanish, and German, but only one or two characters would speak these languages, while the others retained their own language. This practice is referred to as “Il Giro” or “Multilingualism.”

- The Mask: it is mandatory only for Dottore, Magnifico, and II° Zanni. For I° Zanni and Capitano, it is optional and left to the actor’s choice. However, the “Principle of the Mask” applies to all characters: with or without a mask, the actor must respect the gestural and behavioral rules that define each character as a distinct Mask.

- Repertoire: Commedia dell’Arte is not a “theatrical genre”; it is a system for creating and distributing professional theater performances. The Repertoire includes: Fabula Comica, Fabule Poetiche (Pastorale, Boschereccia, Marinaresca, Piscatoria, Tartarea), Opera Eroica, Opera Storica, and Opera Regia (it refers to Tragedia). This extensive range of genres, all rigorously “improvised,” is performed in three acts for the Comica and Poetiche, and four or five acts for the Operas. Each act lasts approximately one hour, with intermissions where the audience is entertained through music and product sales. These are large-scale performances, often with elaborate scenes, costumes, and accessories.

All of this originated in Northern Italy, then spread across the entire Peninsula and the major islands. Eventually, the Comedians spread to the continent, sharing their Arte. Commedia dell’Arte invented everything that is now considered standard practice for theater artists worldwide.

Antonio Fava

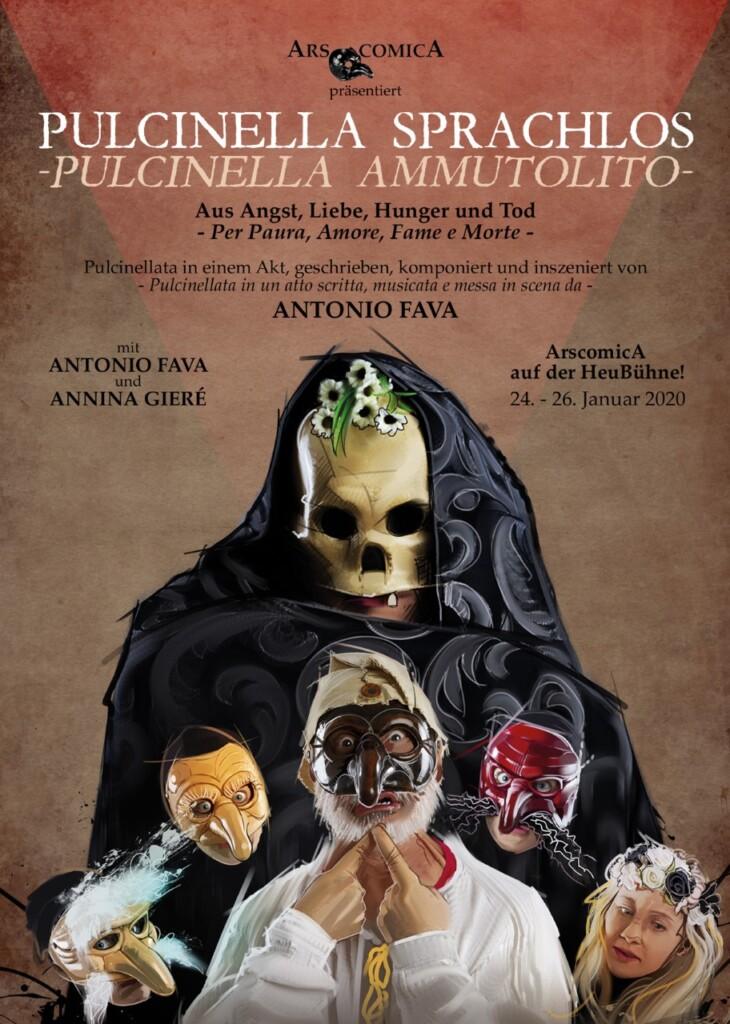

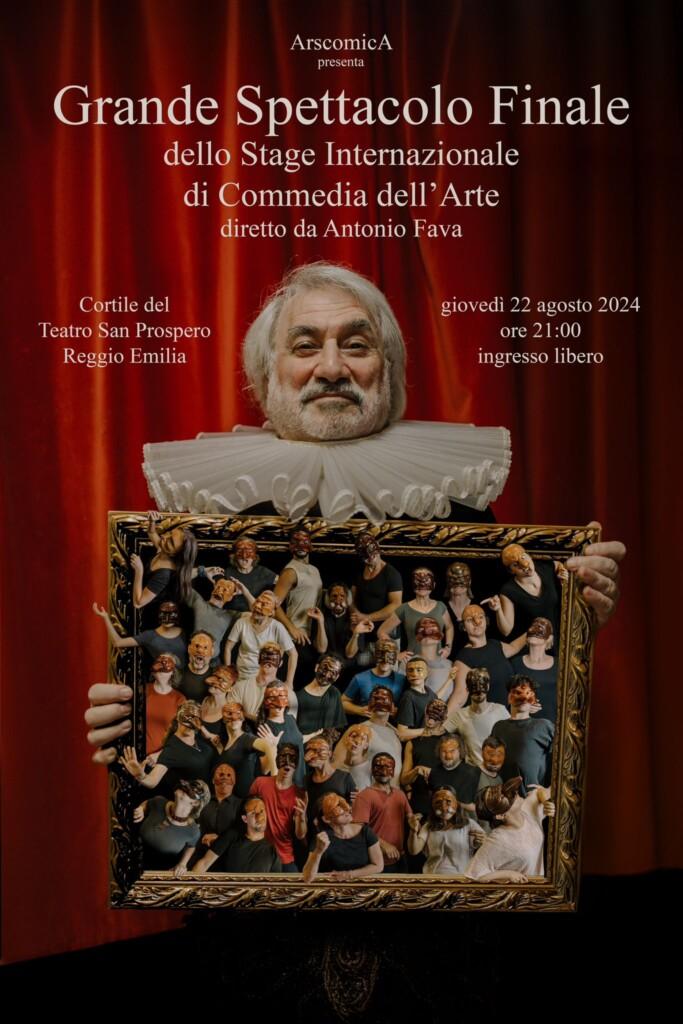

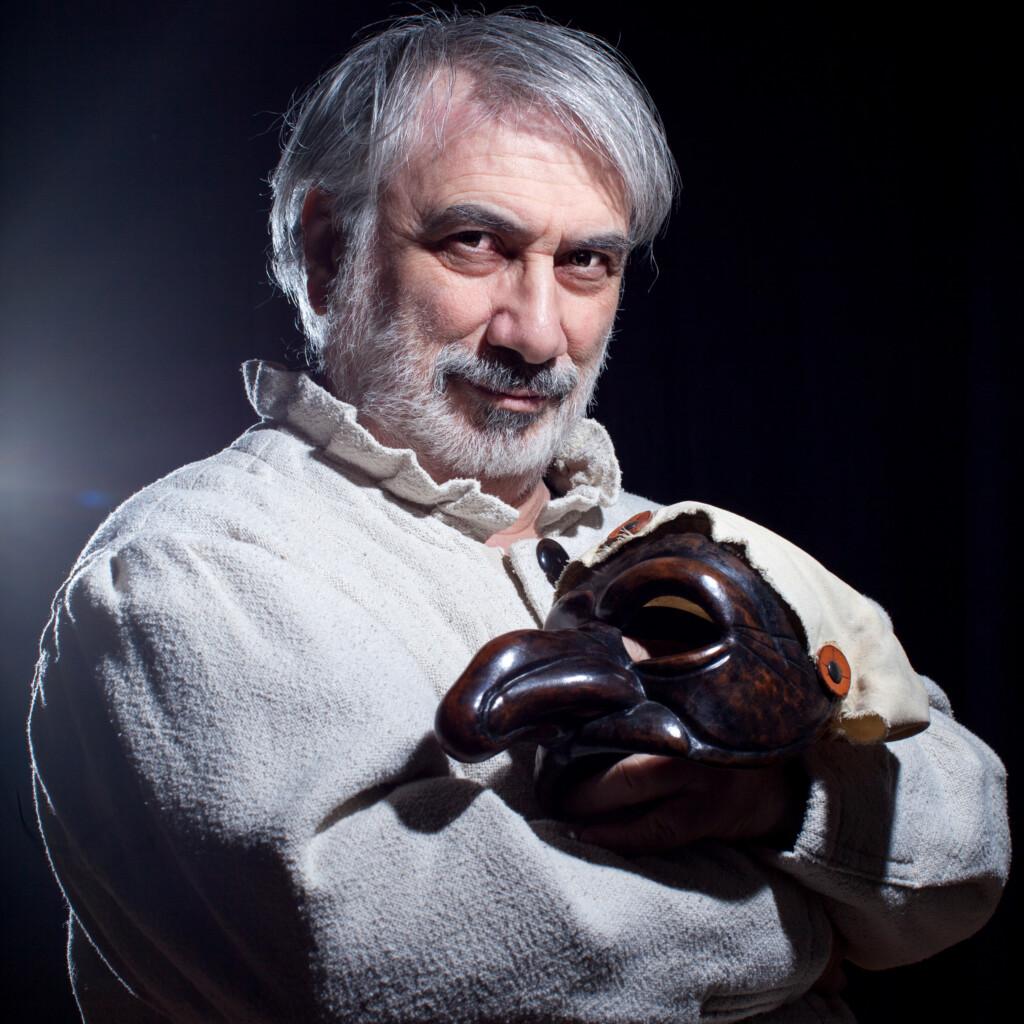

Defined by John Rudlin as a “Renaissance man”, referring to his artistic versatility, Antonio Fava is an actor, playwright, director, flutist, composer, and sculptor. He writes texts for the theater and essays on theater.

A victim of the 1968 movement, like many others, he opposed everything, broke with everything, and proclaimed himself free and independent. Did he do wrong? There and then, yes. However, due to the results of his research, he is now esteemed and recognized as a master in the theatrical field, particularly in Commedia dell’Arte, the knowledge and practice of which he has continuously developed up to the present day (and beyond…).

He gained various experiences, all during his youth, including acting with Dario Fo, Jacques Lecoq, and co-writing with Jean-Pierre Chabrol, but the two main masters who shaped him remain his father, Tommaso, who passed down to him the authentic popular Pulcinella, and the great Maestro Gianfranco Masini, who taught him that he could compose music, if he wished.

In music, Fava is irredeemably tonal and classical. His music accompanies all of his performances. He is a musician by birth and will be one until the end.

He has corrected (or attempted to correct) several misconceptions about Commedia, such as “the street,” improvisation as the “goal” of the actor on stage, or the notion of the absolute character that disregards the ensemble structure of Commedia, where all are protagonists—the actors and the characters. These are false myths that trivialize and de-professionalize Commedia dell’Arte.

He carves and creates the masks for his fabule and for his school.

He is an international director.

His Scuola Internazionale dell’Attore Comico, active since 1984, has trained numerous artists who have acquired the Arte and spread it worldwide.